Patrick Mahomes: The Next Bo And Deion?

The mystery of why two-sport megastars vanished in the 1990s.

Soooo I’m really excited to share the news that I’ll be doing a series of collab stories with my sportswriting hero Joe Posnanski, who has built a truly outstanding Substack called Joe Blogs AND has a new book coming out WHY WE LOVE BASEBALL. For me, this is insane.

We were having lunch the other day at our favorite diner in Charlotte and I floated the idea of working on a story together. To be honest, I was praying he wouldn’t laugh in my face and say ‘beat it, kid’ like they do in the movies. But after pitching the following story, Pos said he didn’t want to work on a story together — no, he wanted to work on stories together REGULARLY. So: crap. Now I gotta not embarrass myself on a REGULAR basis.

If you’re one of the few people on Earth who haven’t already subscribed to his brilliant Substack, go do that now. No one is more prolific and joyful and insightful writing about sports and life than Pos. (His two daughters also happen to be pretty great babysitters for my two daughters. Which means I have to be extra nice so they keep coming back.)

So here’s the first collab, which has Pos’ clearly-marked musings throughout.

Patrick Mahomes is one of the faces of Netflix's new QUARTERBACK documentary series, a behind-the-scenes look at how he and two other NFL quarterbacks, Kirk Cousins and Marcus Mariota, approach their craft. By all accounts, it’s been a hit.

As I’m watching this Quarterbacks series, I can’t get something out of my head. It occurred to me that Mahomes probably could have been a Bo Jackson, or a Deion Sanders, for today’s generation – the two-sport megastar. Mahomes was an incredible baseball player growing up and even got drafted into Major League Baseball. But he gave it up to pursue a football career.

As the documentary steered its focus to Cousins and Mariota, my mind wouldn’t leave Mahomes. I was wondering, well, why not – why didn’t Mahomes do the two sport thing? And really, why in the world haven’t we had one since the 90s? The two-sport star and Zubaz pants — both peaked in the early 90s and never returned.

I began stewing on this mystery in the second episode of Quarterback, which opens with a surprising theory for why Mahomes has mastered the game of football. He’s shown at a gala presented by his foundation, sitting down with a nine-year-old student.

“When you were a kid,” the boy asks him, “what did you really want to be? A football player or …”

“When I was a kid, I did not want to be a football player,” Mahomes tells the boy. “I wanted to be a baseball player. My dad was a baseball player and my dream was to play baseball. I grew up playing baseball and I thought kinda that was going to be what I did.”

The documentary shows highlights of the lesser-known Patrick Mahomes, his father, Pat, who enjoyed an 11-year career as a Major League Baseball player. Pat came up through the Minnesota Twins organization and pitched as a top reliever for the New York Mets in the 1999 playoffs. We see a young Patrick Mahomes bopping around as a little kid on the field in a Mets jersey pretending like he’s a major leaguer. It’s a touching scene that I’ve watched hundreds of times with young Stephen Curry and his father Dell, or young Prince Fielder with his father Cecil.

On Quarterback, the Mahomes baseball detour doesn’t function as a brief nod to his father, which, gotta admit, is a cool tidbit that I had forgotten about. Instead, Mahomes’ baseball upbringing is everything. He talks about his signature “unscripted, off platform” throws as a quarterback — the side-arm, varied-angle throws that sets him apart from the more conventional Tom Bradys of football lore — and says it feels totally natural to him. “They’re baseball throws to me,” Mahomes reveals. We see in the documentary that Mahomes even swings a bat from both sides with more power than basically anyone his trainer has ever seen.

And then it hits me: Patrick Mahomes might be so great at football because he’s great at baseball.

*JOE: Hi, Joe here. Here’s something funny; I spent a little time talking with Patrick Mahomes last week for something I’m working on at Esquire. And I did ask Patrick about this exact thing — if he thinks that his skill at baseball is what separates him as a quarterback.

He talked about — as he does on Quarterback — exactly what Tom is talking about here. Playing baseball, especially shortstop, has played a huge role in the way he plays quarterbacks, with all the amazing sidearmed throws. “When you’re trying to turn the double play,” he said, “you just get the ball to the second baseman any way you can. So I definitely brought that to football.”

But the funny thing is — he now thinks that the role baseball plays in his football success is getting overplayed … and the part that gets underplayed is what he brought to football from his BASKETBALL playing days.

“Playing point guard in baseball really influenced how I play quarterback,” he says. “That’s really more the same than baseball. You’re trying to pass it to the guy in the right spot. You have to play in space. You have to identify who is open while everything is in motion. I think basketball had a huge influence on how I play quarterback.”

Mahomes once threw a 16-strikeout no-hitter dueling against Michael Kopech, who’s currently a starting pitcher for the Chicago White Sox. Mahomes played the second game of a doubleheader that day and went 3-4 with a homer, a double and three RBIs. He was drafted in the 37th round of the MLB draft, though he never went pro on the diamond. (And yeah, he’s pretty good at basketball too but the Chiefs won’t let him do that anymore. BOO.)

And it’s all a mystery to me. Why not Mahomes? Were Bo and Deion once-in-a-century athletes that randomly happened to play at the same time?

Or were they the start of something that got derailed?

Bo and Deion

If you were a kid growing up in the 90s, you knew about Tecmo Bo. In the NES game, Bo Jackson was basically a cheat code, faster than everybody else and could break just about any tackle. Slip into the open field in the game and Jackson could zig-zag his way to the endzone. Because of this, no one in my basement was allowed to play with the Raiders.

*JOE: Funny, in our basement, nobody was allowed to play with the Dolphins because there was a particular Marino to Duper pass that was literally unstoppable. It was a glitch in the game. Meanwhile, yes, Bo was incredible but that team also had no passing attack, and their defense other than Howie Long was absolutely atrocious (we used to have Howie Long drop back into coverage; he was the best defensive back on the team as well as the best lineman). So you were allowed to play with the Raiders. In fact, when Bo’s condition was “poor,” it was almost impossible to win with them.

The video game reflected the reality of trying to bring down Bo Jackson. There’s the famous 91-yard touchdown from his rookie season which ended up with him running through the back of the endzone and vanishing into the tunnel. Pull up his player profile on Pro-Football-Reference and you’ll find that in his four seasons in the NFL, he registered some incredible runs – a 92-yarder, a 91-yarder and a 82-yarder – all season-highs for any player that season. To put that in perspective, Emmitt Smith never recorded a run longer than 75 yards in his 15-year career.

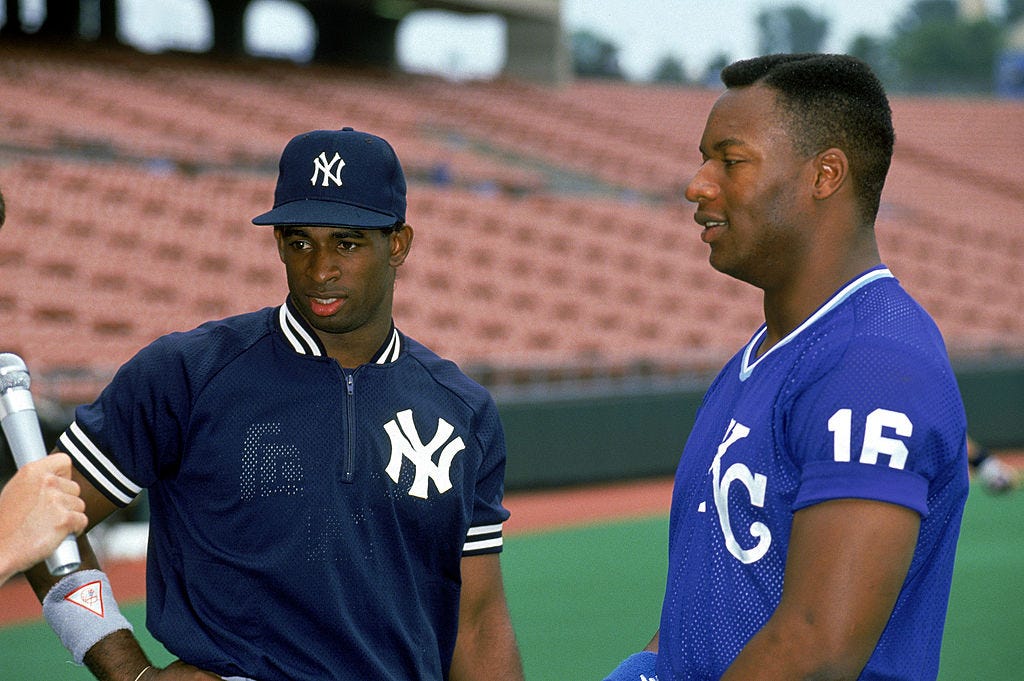

I remember collecting Bo Jackson’s baseball cards with the Kansas City Royals and thinking that a player going pro in two sports was normal. Jackson’s MLB career spanned from 1986 to 1994 while his NFL career went from 1987 to 1990. It just so happened that a Florida State Seminoles star from Fort Myers named Deion “Prime Time” Sanders did the two-sport thing at the same time, playing in the NFL from 1989 to 1999, with his MLB career spanning from 1989 to 1994. (should note: Sanders returned twice to MLB and then came back to the NFL for two seasons in 2004 and 2005 with the Baltimore Ravens).

It seemed like Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders spawned a whole cross-sport movement. As a kid, I distinctly remember watching a VHS tape of the 1992 Celebrity Slam Dunk contest that showed Sanders, Michael Irvin, Ken Griffey Jr., Barry Bonds and Cris Carter flying all over the place and dunking off-the-backboard, off-the-bounce with legit NBA flair. Someone uploaded the full hour-long ABC broadcast to YouTube. It’s incredible. Dick Vitale and Jimmy Valvano did the commentating. Wilt Chamberlain did the judging. This was like mainlining 90s nostalgia.

I mean, here’s Ken Griffey Jr at 21 years old:

There was a track-and-field athlete who dunked from two inches behind the free-throw line. The best part was that he got so excited he pulled it off that he ran down the court and got kicked in the face after running into a cheerleader doing a backflip thing.

That guy?

Mike Conley. Yes, Mike Conley Jr.’s father. He was one of those freak athletes. (I must point out that Mike Conley Jr., hasn’t dunked a basketball in years).

Of course, Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders weren’t the first ones to excel at multiple sports. Back in the day, Jim Thorpe, Jim Brown and Jackie Robinson were dominant in a zillion sports. John Elway (NFL and MLB), Tony Gwynn (MLB and NBA), Tom Glavine (MLB and NHL) and Dave Winfield (MLB and NBA) were drafted in multiple pro sports. But they gave up one to focus on another. They weren’t Bo and Deion.

Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders didn’t just play two sports in the pros. They were awesome at them. Go read Pos on Bo Jackson. I had the privilege of seeing an early copy of his Bo Jackson entries in the upcoming Why We Love Baseball book (yes, preorder now!) and let me just say I still can’t believe he was a real person. And I watched him with my own two eyes.

JOE: I did not pay for this endorsement.

You could say similar things about Deion. In 1989, Deion hit a home run for the New York Yankees and scored a touchdown for the Atlanta Falcons in the same week. Deion Sanders once led the majors in triples with 14. That’s not the crazy part. Here’s the crazy part: he missed 65 games that season. OK, that’s not the craziest part. Here’s the craziest part: he hit six doubles. That’s right: he hit over two times as many triples as doubles. I don’t think anyone has ever come close to doing that. I don’t even know if that’s a good thing. I just know it’s something we’ll never see again.

*JOE: I was lucky enough to cover Deion when he was with the Cincinnati Reds; and it struck me how much DIFFERENT he was as a baseball player from his remarkable football persona. There was no Neon Deion on the baseball diamond; Sanders was one of the hardest-working and modest baseball players I’d ever covered. He seemed to understand that baseball required something different from him; in football, he was untouchable as a kick returner and cover corner. But baseball was harder, particularly at the plate. He willed himself into becoming a pretty good baseball player, but it wasn’t easy.

Bo and Deion were so good that they seemed like they were going to inspire whole generations of Bo Jacksons and Deion Sanders’. They punctured through pop culture and became household names. They were huge. They were everywhere. And then it just kinda … stopped.

So what happened? Why haven’t we seen Patrick Mahomes try his hand at being Bo and Deion? Or why hasn’t LeBron James or anyone else? I don’t think I have one tidy theory. There are a bunch of factors. Let’s run through them one by one.

Theory 1: We live in a Specialized World.

My first thought was that we should blame the era of specialization. The thinking goes, if you want to be great at something, you have to specialize early and stick with it. In this world, sports are no longer a seasonal hobby; they’re a year-round vocation.

In high school, Danny Ainge was a first-team All-American in three different sports, baseball, basketball and football — the only athlete to ever pull off the trifecta. He played in both the MLB and the NBA. Great. But that was almost 50 years ago.

Ainge barely played AAU basketball before he went to the NBA. Nowadays, there’s sponsorship money pouring into AAU teams at the youth level. National rankings for AAU teams begin in the first grade. This is a race and you better get a head start. Didn’t you hear about Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-Hour rule?

Just about every NBA player played some level of AAU so getting them into the program early might seem like a wise decision. But you risk burnout and other not great outcomes. The opportunity cost of a child “picking” a sport as a nine-year-old can far outweigh the benefit. Opportunity cost is the benefit you lose out on when you choose one option over others.

A nine-year-old spending an entire year on an AAU circuit for an unlikely NBA career could mean they miss out on a potential big-league baseball career. Maybe the kid is better at hitting a curveball than a jump shot. You’d never know.

In Gladwell’s 2008 New York Times bestseller Outliers, he argued that the icons took about ten years, or roughly 10,000 hours of practice to get there. From chess grandmasters to Bill Gates to The Beatles, if you want to be a phenom at something, you need to put the blinders on and practice that one thing over and over and over. “Ten thousand hours,” Gladwell wrote, “is the magic number of greatness.” You can understand the lesson for someone with dreams of becoming a pro athlete. If you want to be drafted at 20, better dedicate yourself at 10.

David Epstein’s first book, The Sports Gene, published five years after Outliers, spent some time re-evaluating Gladwell “10,000-Hour Rule.” Epstein’s follow-up Range: Why Generalists Triumph In A Specialized World was an entire book that expounded on the subject, taking a deep dive into the backstories of the world’s greatest fill-in-the-blank and found that they were more often generalists, not specialists, at a young age. (Bill Simmons hosted a fascinating conversation with Gladwell THIS WEEK about why youth sports is broken.)

It only takes a few minutes watching that 1992 Celebrity Dunk Contest to see that Cris Carter, Ken Griffey Jr., and Deion Sanders were more generalists than specialists. Maybe today’s MLB and NFL stars could do similar things on a basketball court but it’s undeniable that cross-sport skill isn’t celebrated or encouraged like it used to be.

I caught up with Epstein over email while he was traveling overseas on a reporting trip. I asked him if he had an answer for why Bo Jacksons haven’t popped up in decades. For the most part, he was stumped.

“That’s a really interesting question,” Epstein says. “I don't think there's any doubt that a Patrick Mahomes, or a Russell Wilson, or a Kyler Murray or others could do it.”

Like with everything, you have to follow the cash.

Theory 2: There’s too much money at stake.

Wilson and Murray have both been drafted by MLB teams, but pursued a quarterback profession that seemed to have a shorter runway to riches. From a baseball family, Murray was the better baseball prospect, even drawing comparisons to Rickey Henderson. Drafted ninth overall in the 2018 MLB draft by the Oakland A’s, Murray inked a $4 million signing bonus with the club, but delayed his baseball career to focus on football. He won the Heisman the next season and became the No. 1 overall pick in the NFL draft, netting him a $24 million signing bonus. A few years after turning his back on baseball, the Arizona Cardinals signed Murray to a five-year, $230 million contract with about $160 million guaranteed. So I guess you could say the decision paid off.

Epstein says even if the Mahomes’ of the world wanted to play another sport, he’d have to get clearance from the leagues and teams. Milwaukee Bucks forward Pat Connaughton, who was drafted by the Baltimore Orioles in 2014 because of his 96 mile-an-hour fastball, could probably start for an MLB team right now, but the NBA team that drafted him in 2015 wasn’t on board with him going for two.

“That’s not happening,” said Neil Olshey, the GM of the Blazers told NBA.com at the time. “Being an NBA player is not a part-time job.”

*JOE: I think there’s a lot here — truth is that anytime anyone wants to do something REMARKABLE (looking specifically at Shohei Ohtani), they kind of have to fight the system and will themselves forward. Nobody wanted to let Ohtani hit and pitch; but the Angels realized that encouraging him was the only way he would sign with them. Nobody wanted to let Bo play football and baseball, but neither the Royals nor Raiders really had a choice in the matter.

Connaughton gave up baseball and is set to eclipse $50 million in career earnings as an NBA rotation player. Maybe he goes back to the mound one day. Territorial leagues is a primary reason why Epstein isn’t bullish on the idea of Mahomes being allowed to dabble in baseball. “I have a hard time seeing that happen,” he said.

Ainge, talking to former NBA players Quentin Richardson and Darius Miles on the Knuckleheads podcast last week, talked about the contractual conflicts between leagues. When Ainge was drafted by the Boston Celtics, he was ecstatic to join the defending champs. There was only one problem: he was still under contract with the Toronto Blue Jays and the legal fine-print said he wasn’t allowed to play basketball. Led by Toronto’s president Pete Bavasi, the Blue Jays sued the Boston Celtics in federal court and won. The best part of that whole thing? From a 1981 New York Times story:

After the jury had announced its verdict, Bavasi lighted a cigar and recalled Auerbach's habit of lighting cigars to celebrate Boston victories on the basketball court.

Amazing pettiness. The Celtics ended up forking over a bunch of money to the Blue Jays and that was that.

In looking up these stories, I’ve found that two-sport stars can use their other sport as negotiating leverage. Ainge told teams leading up to the NBA draft that he wasn’t going to play basketball and scared them away. Ainge secretly wanted to play for the Celtics or the Los Angeles Lakers. The Celtics came calling and his master plan worked.

Bo Jackson experienced his own high-profile dispute with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, the team that drafted him No. 1 overall in the 1986 NFL Draft. A two-sport star at Auburn, Jackson accepted a visit to Tampa Bay paid by the Bucs thinking it wouldn’t violate SEC amateur regulations, but it ended up terminating his Auburn college baseball career early. The public humiliation angered Jackson so much that he sat out the entire NFL season refusing to play for Tampa Bay. Al Davis and the Los Angeles Raiders selected Jackson the following NFL draft and the rest is history.

World-class athletes feel financial pressure to specialize as adults. Epstein points out that two-time Olympian Devon Allen is “probably one of the best three sprint hurdlers in the world now, and has left that behind.”

Why? “Just to avoid conflict with the Philadelphia Eagles practice squad.”

Making an NFL team could net him a paycheck of $750,000 or more. First-place medals at World Championships (he has three of those) may be made of gold but not that much gold.

It’s not just pro-money that forces athletes to choose early. Think about the skyrocketing cost of college tuition. Sampling a bunch of sports sounds good in theory, but try selling the generalist idea to someone who struggles to put food on the table, much less fork over $200,000 to send their kid to college. If a kid can throw 90 miles an hour with movement, why mess around with that lottery ticket and put a basketball in his hand?

This makes a lot of sense to me. And Epstein too.

“I'd guess that with the way incentives are now, the incentives for an athlete to maximize in one area is just much greater, combined with incentives of other people to try to push them into a single lane.”

Theory 3: Football is too dangerous.

Before LeBron James became “The Chosen One” on the cover of Sports Illustrated, he earned his way to become a two-time All-State football player in Ohio, for all the same reasons he’s one of the top two basketball players ever.

Here’s a snippet from that SI feature by the late, great Grant Wahl:

For the last two years, in fact, he has risked career-threatening injury as an all-state wide receiver on the St. Vincent-St. Mary football team. At first Gloria refused to let LeBron play last fall, but after the 22-year-old singer Aaliyah died in a plane crash last August, he persuaded her to let him play. "You're not promised tomorrow," LeBron says. "I had to be out on the field with my team." Though LeBron did break the index finger of his left (nonshooting) hand, he helped lead the Irish to the state semifinals.

It’s not preposterous to think that LeBron, standing 6-foot-8 and 250-plus pounds, could have enjoyed a long career as a tight end in the NFL. In fact, an anonymous NFL general manager once told NFL reporter Mike Freeman that "LeBron James would have been the best tight end of all time. He would have been Rob Gronkowski before Rob Gronkowski. No one would be able to cover him. He would have set records every season."

Another scout told Freeman that James would have been a top-10 player in the sport of football. Ever.

*JOE: LeBron, because he was (and still is) such an extraordinary athlete with such extraordinary skills (such as his unmatched vision), fosters these sorts of over-the-top statements. Would LeBron James REALLY have been a great football player? Who knows, right? But I’ve heard the same thing said about him as a soccer player; that if he had chosen soccer he would have completely reshaped the entire sport.

James has said before that he misses playing football every day. He may have had a higher ceiling in basketball, but it’s clear that potential wasn’t the only thing holding him back from playing football. It’s the same reason that his mother Gloria wanted him to walk away from the gridiron entirely. It was just too dangerous. What if he got hurt? (LeBron once told my pal Jonathan Abrams that he would have played both football and basketball at college.)

Charlie Ward won the Heisman Trophy at Florida State and was drafted in Major League Baseball twice; he chose to play in the NBA instead. At Wake Forest, quarterback Rusty LaRue broke eight NCAA passing records including most completions in a game (55). He went to the NBA and won a championship with the 1998 Chicago Bulls. While those decisions were made in part because they may have envisioned brighter futures in basketball, I find it hard to believe that the violence of football didn’t play some small part in the decision to leave it behind.

But that math doesn’t work for everyone. Randy Moss, who was voted West Virginia’s best high school basketball player two years in a row, remembers quitting basketball to focus on football after a pickup game with Kevin Garnett. Moss played him one-on-one and got blocked so badly by Garnett, it ruined Moss’ drive to play hoops anymore. “Man, he can jump that high?”

In a KG21 interview on TNT, Garnett mentioned to Moss that Antonio Gates and Tony Gonzalez played basketball at a high level before dedicating themselves to the gridiron. Upon hearing those names, Moss surprisingly argued for a generalist mentality: “These athletes nowadays need to leave all their options open and not just take one sport.”

Still, football wasn’t so dangerous that Moss regrets giving up basketball. When Garnett asks Moss if he’d choose hoops given what he knows now about concussions, Moss said the love for football trumps all. No regrets.

But KG doesn’t ask the real question: why not both?

Theory 4: Pro sports are just too advanced now to split time.

Athletes are bigger, faster and stronger than ever. It stands to reason that as each sport becomes more sophisticated and skilled, it would be harder to switch lanes and keep up.

It’s one of the reasons that Connaughton was barred from playing for the Orioles. Here’s Olshey:

“The time when Pat would be going to play baseball is a time when you’re working on your game and getting better. You see how valuable July is. During the development phase, when you’re a second-round pick in the NBA and you have a ways to go to have a translatable skill-set in our league, you need Summer League, you need Grg’s camp (run by Bucks assistant Tim Grgurich), you need to spend the offseason in the gym. You can’t do that on a part-time basis.”

Maybe it was easier to pick things up in the 80s and 90s. Ainge mentioned how scared he was that he made the wrong decision when he joined the Celtics in 1981.

Because of the Blue Jays dispute, Ainge missed Celtics training camp and the first month of the season. (Another pothole in the two-sport plan; Bo Jackson missed eight weeks of his rookie NFL season because he was finishing up his work with the Kansas City Royals). Ainge tells the story about how his Celtics teammate Cedric Maxwell sat on a stage, taunting Ainge, during Ainge’s first practice in December of his rookie season. The team was 15-4, rolling through the league, and here was this Toronto Blue Jay trying to prove he could cut it in the NBA. Fresh off baseball season, Ainge was getting up some shots by himself. And missed and missed and missed.

“Cedric is sitting on the stage,” Ainge recalls, “counting out my shots, saying, ‘3 for 11 …4 for 15 … 6 for 21...’”

Ainge was embarrassed. These were open shots. No one was guarding him. And he couldn’t hit them? He remembers the Celtics’ coach Bill Fitch, fresh off an NBA title, walking over to Ainge while Maxwell was egging him on.

“It’s not as easy as you thought it was going to be,” Fitch said to Ainge.

I tell this story because Ainge averaged just 4.1 points per game his rookie season. He was not good. But he became good. Six years later, he made the NBA All-Star team.

Michael Jordan had a .556 OPS in his lone season at Double-A baseball, which, on the surface, looks awful. But that’s too harsh. To me, Jordan hitting 31 extra-base hits and stealing 30 bases in pro ball after not playing the sport competitively in over a decade is a gob-smackingly impressive feat. After all, Ainge shot just 35 percent as an NBA rookie and then enjoyed a 14-year career once he got his feet underneath him. Maybe Jordan could have done the same if he stuck with it. Nonetheless, MJ let Deion and Bo handle the two-sport thing.

*JOE: I was lucky enough to see MJ play baseball in Birmingham. It’s hard to say what a 31-year-old minor leaguer could still do, but I tend to agree with Tom — the amazing part was not that he struggled and hit just .202. It’s that he hit Class AA pitching at all after years and years of playing basketball and no baseball. He was fast, a good outfielder, if he had concentrated on baseball from the start I think he’d have had an excellent shot at being a big leaguer. And if he’d stuck with it for another year or two, he might have made it up to the big leagues, even for a cup of coffee.

There’s another thing about Ainge I should mention. He wasn’t a very good major leaguer. In his third (and final) season in the majors, he hit .187 in 246 at bats and finished with an OPS+ of 38 where 100 is average. I looked it up: no hitter this season has an OPS+ that low with as many plate appearances as Ainge had in 1981. Maybe the NBA was a life raft.

So yeah, maybe playing two pro sports at the same time is just too hard. Or maybe it’s too hard for people not named Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders. But something else has gotten harder in recent years.

I’m imagining a world in which LeBron throws on shoulder pads and suits up for the orange and brown in Cleveland. Let’s say it takes LeBron a season to figure things out. (Recall that Bo Jackson had an OPS+ of 67 his rookie season for the Royals). Would LeBron have the mental resilience to endure the social-media onslaught and taunting from his peers if he drops a few passes or allows an interception because he butchered a route? Is that media hailstorm something he’d willingly walk into?

The LeBrons and Mahomes’ of the world may be able to handle public humiliation in their First Pro Sport because they have championships and records to fall back on. Absorbing the ridicule and dealing with requisite failure in the Second Pro Sport may be too bewildering without the comforting safety net buttressed by a career of accomplishments. They’d likely need a season of failure before they could really shine. Would they have the stomach to get the other side?

Bo Jackson, Deion Sanders, Michael Jordan and Danny Ainge were able to strike out, fumble and double-dribble before the advent of the Internet and its vicious social media. Skills aren’t the only thing that has advanced in the last half-century. So has the megaphone of scrutiny.

Fantastic article! Surprised you didn’t bring up 2-sport Atlanta legend Brian Jordan

Also: Guys just want an offseason. They can rest and recover, travel, spend time with family, take on endorsement trips, all of that.