Did Chauncey Billups just invent the basketball closer?

The curious case of Dalano Banton, the fourth-quarter specialist.

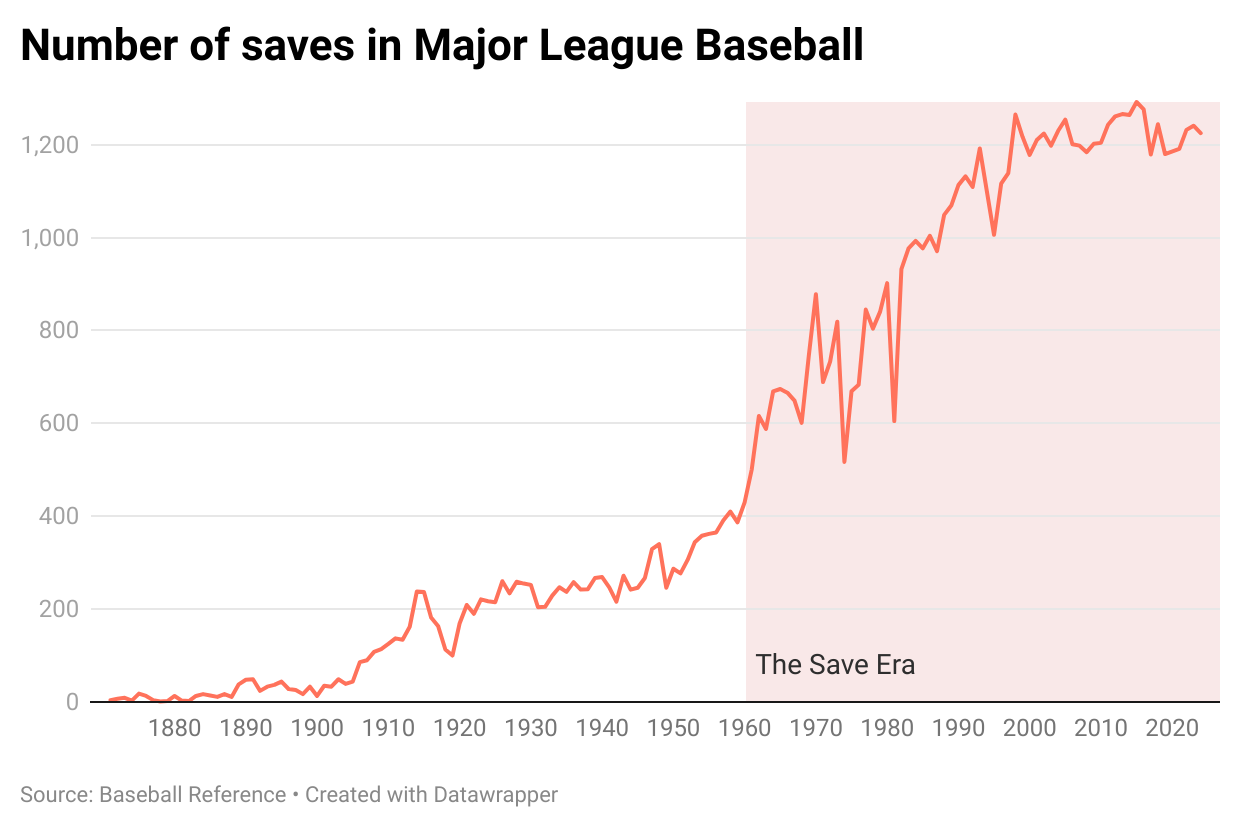

In baseball, the notion of a closer is a relatively new phenomenon. The World Series began in 1903, but the save didn’t become an official statistic until 1969, a handful of years after famed sportswriter Jerome Holtzman1 popularized the concept at the Sporting News. In the ‘70s, Goose Gossage and Rollie Fingers became stars in this oddball role, sitting in the bullpen and waiting for the manager to call their names and close the door.

It might be hard to envision baseball B.S. (Before Saves). For almost seven decades, the sport didn’t bother tracking saves, what is now considered one of the most lucrative and valuable trades in America’s pastime. It took even longer than that for closers to be deemed Cooperstown material (in 1985, Hoyt Wilhelm was the first ace reliever to be inducted into the Hall2).

For most of baseball’s existence, the closer just wasn’t a thing. Here’s my pal Joe Posnanski writing for MLB.com in 2017:

The save has fundamentally changed baseball in the past 50 years. This was not Holtzman's intention, of course. He just wanted a quick and easy statistic that measured a relief pitcher's contribution. Holtzman had no idea that his little invention would create a whole new kind of ballplayer, earn unsuccessful starters and pitching specialists hundreds of millions of dollars, inspire a generation of young men to throw 100 mph and get managers to reinvent how they use their pitching staff.

I offer that history lesson as perspective on what’s happening in Portland with Chauncey Billups and Dalano Banton.

On Monday night, the 6-foot-9 Banton sat on the bench until the start of the fourth quarter. The Blazers were down three points, needing a jolt.

So, Billups put in Banton.

Banton scored 20 points that final quarter. He walked on water. The Blazers won by 18.

Game over.

As the analytics insider for the Blazers broadcast, it’s my job to pop onto the screen every once in a while and offer kernels of insights into what’s happening on the floor with cutting-edge statistics and analytical tools. When Banton started getting going in the fourth quarter, the light came on.

This guy seems to only be doing this in the fourth quarter this season. How freaking strange is that! Is this really happening?

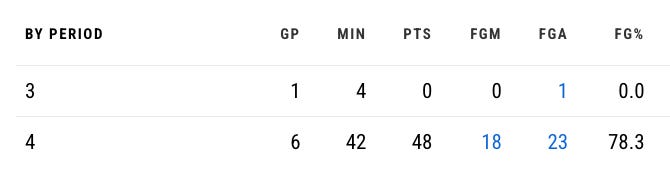

I started digging. I looked up his quarterly splits. How many points has Banton scored in the first quarter vs. second quarter vs. the third quarter vs. the fourth quarter? I was prepared to run the numbers and see if I could find out whether Banton’s proportion of points coming in the fourth quarter was the highest in the league. As I clicked around, my stomach sank as I found a glitch in the NBA.com system.

This can’t be right, I thought. The quarterly splits weren’t showing Banton’s first or second quarter stats. Just third quarter and fourth quarter numbers. I refreshed. Same thing. Shit.

It suddenly dawned on me. Wait. Banton hasn’t even played in the first or second quarter. There was no glitch. THERE WERE NO STATS TO LIST.

And then … WAIT, ALL OF HIS POINTS ARE IN THE FOURTH QUARTER???

I started pinging my producer Greg Fonseca.

“Greg, I think I have something here on Banton,”

“What’s that?”

“Just get it to me, on Banton’s scoring.”

Moments later, Kevin Calabro THE LEGEND got it to me:

Calabro’s giggle at the end is so great. The best.

ANYWAY: By the time the hit aired, Banton had tallied eight points in the quarter, enough for me to grab Greg’s attention. Over the next eight minutes, it kept coming. And coming. Banton would go on to score 12 more points in whirling fashion, turning the Pelicans’ lead into dust. Lamar Hurd, the ever-sharp Blazers analyst, called Banton “The Secret Weapon.”3

I should mention here that, yes, duh, we are part of the Blazers broadcast. I’m not going to sit here and disagree with you if you think we may seem biased toward Rip City’s players. I get it. But our closeness also gives us an advantage in spotting something that non-local folks might miss when they’re flying by on a Monday night.

Because here’s the thing: we’ve watched Banton do this again and again.

On Friday, Banton entered the game in garbage time against the Thunder, who were up 21, and immediately he turned the game on its head. He blocked a shot and then scored the next five points. The Blazers went on a 13-4 run largely on the back of Banton’s playmaking and rim attacks. The Thunder, my preseason pick to win it all this year, pulled away because that’s what they do. Banton finished with 11 points and three assists in nine minutes. OK.

On Saturday, the very next night, Billups did the same thing. End of third quarter, Blazers down 22, he called on Banton, who hadn’t played in the game yet. And he changed the game again.

Over the next 10 minutes, the Banton-led Blazers made it a one-possession game with 1:33 left thanks to Banton’s heroics. He scored 12 points in a flash and made plays all over the place. The game was now in balance. Devin Booker responded with a nifty jumper. Banton returned the favor with a made 3-pointer. When that went in, I remembered thinking, how is this a freaking two-point game?

Banton is how — the guy they call D.B .Hooper. Which is a perfect nickname. He’s a capital-h Hooper. The Blazers weren’t able to complete the 22-point fourth-quarter comeback, but Banton somehow made it a two point game with a minute left. He was on the verge.

If you want VIP access to Basketball Reference’s research tools, I have a special discount for my subscribers. Use promo code HABERSTAT at Stathead.com, you can get 20% off an annual subscription. Tell ‘em I sent ya.

Two nights later, Billups pressed the Banton button again, the third time in four nights. Think about this. After Banton led the charge against the Suns, Billups didn’t go to Banton early. He waited. And waited. In the fourth quarter, down three, it was time. Billups finally put the game in Banton’s hands, subbing him in for defensive whiz Toumani Camara.

The Pelicans couldn’t stop the guy in their own building. Banton outscored New Orleans by himself 20 to 18 the rest of the way. Portland won by 18. Banton finally closed the door and the Blazers came away with the resounding win.

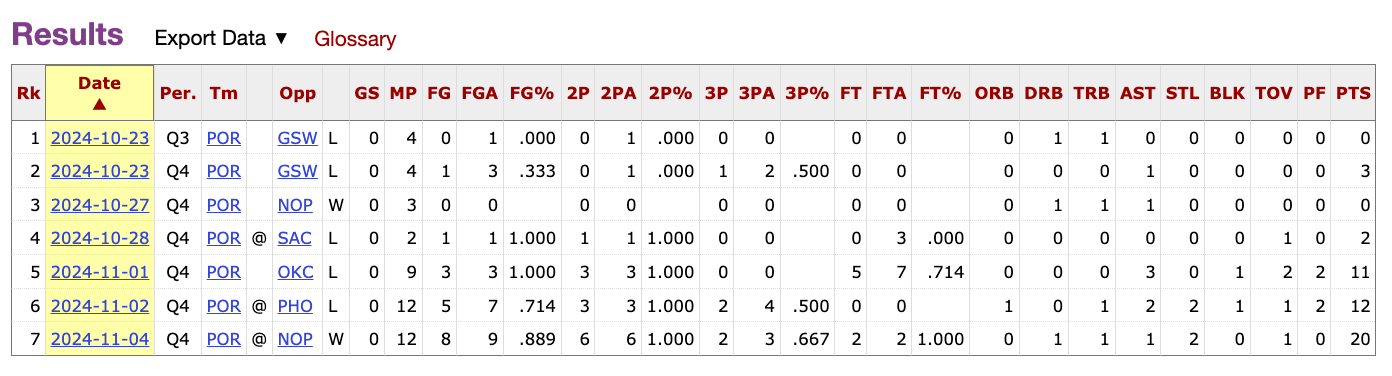

Like I said on the broadcast, I can’t recall seeing anything like this. In the last three games, Banton has exclusively played in the fourth quarter. He has scored 33 points in 33 minutes, shooting 16 of 19 from the floor and four of nine from deep. He’s tallied four steals and two blocks. In those 33 minutes of Bantonball, here is the scoreboard:

Blazers 98, Opponents 54.

Holy smoking lizards. Dalano Banton might not be the best player on the floor for 48 minutes. But in 12 minutes when everyone else’s legs are dog tired, he sure looked like the best player on the floor. And really: isn’t that what a closer is?

We need closers in basketball. Entrance music and everything. I’m ready.

It might seem radical — some might say insane — to believe that a basketball coach would use a player exclusively in late and close situations. But then again, the NBA has been around for about seven decades, the same lifetime that existed before the birth of saves in the MLB. Maybe this isn’t so crazy after all.

I don’t know where Billups takes it from here. Performances like these typically induce a promotion into the regular rotation or even into the starting lineup. But after the OKC and Phoenix surges over the weekend, Billups treated Banton like he was the team’s closer, believing that he’d be a better fit as a finisher than a starter.

“He’s as confident as any player as you’ll ever meet,” Billups said about Banton’s play after Monday’s game. “He just thinks that’s what he’s supposed to do.”

There’s a chance this goes in a different direction and the closer experiment is abandoned. But Banton’s potential as the game’s first closer wouldn’t be as tantalizing if he was just jacking up threes and riding a hot streak. He’s been unstoppable getting to the rim.

The 24-year-old is doing it in such a way that makes you think about what a closer might look like. What a full tank of gas would look like in a game filled with players running on empty.

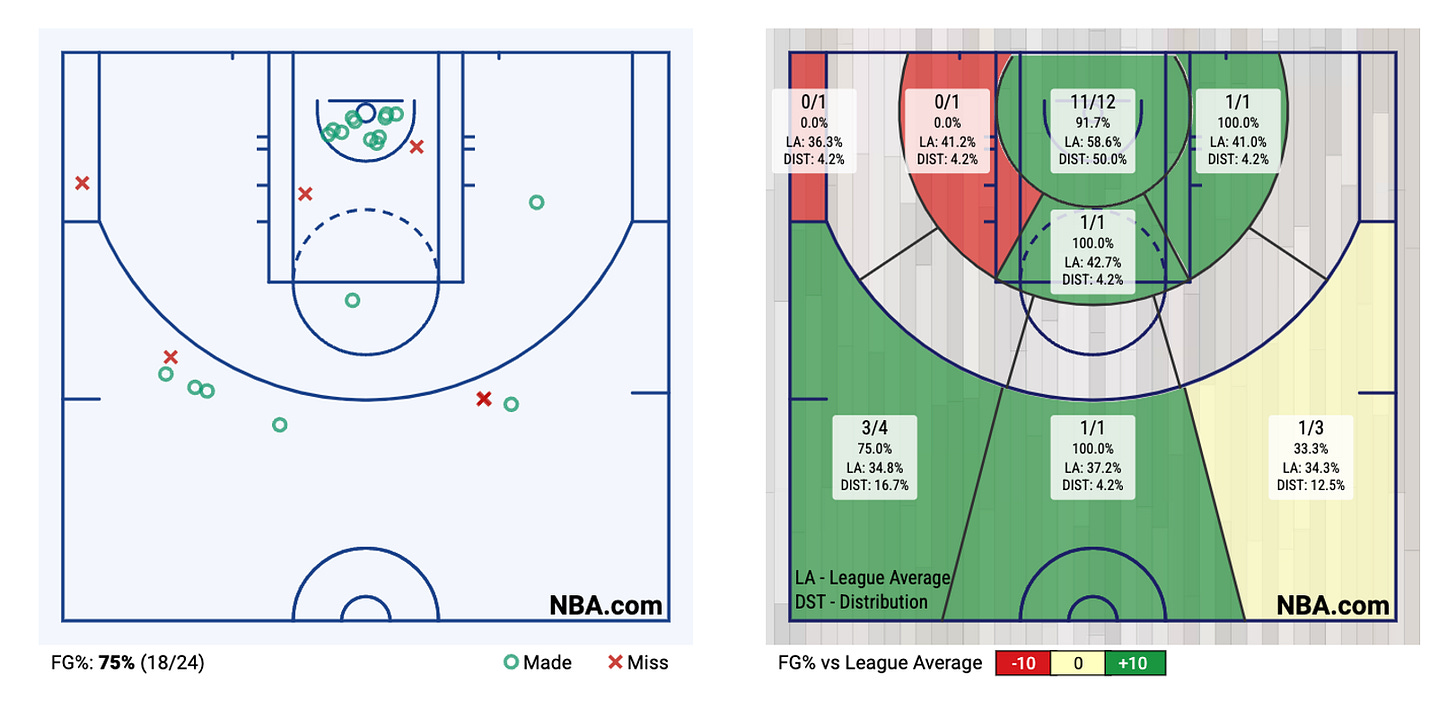

Banton is a 6-foot-9 wiggle machine that snakes his way into the lane at will. If you’re slow-footed in the least bit, he’s gone. Bye. On Monday night, five of his buckets came at the rim off the dribble. Defenders couldn’t stay in front of him. When he gets to the cup, he uses his creativity, length and soft touch to finish over the defense. On the season, he has taken 12 shots at the rim. He has missed one of them.

Look at this shot chart:

One could point to Monday’s performance as a lucky outlier. He was facing a severely shorthanded Pelicans roster that was without Dejounte Murray, C.J. McCollum, Trey Murphy III, Zion Williamson, Herb Jones and Jordan Hawkins. Sure, the Pelicans’ third-string folks were thrust into starting roles and that can wear you down.

A guy like Banton won’t face cinderblock legs every game. But it’s also 100 percent true that starters are fatigued every night in the NBA. If a talented scorer like Banton can come and try to run teams out of the gym like a 100-mph throwing reliever coming onto the mound in a tight spot, that’s a notion worth exploring.

You might say that Banton isn’t the guy. After all, the Boston Celtics essentially gave him away at last year’s trade deadline, trading him to the Blazers for a heavily-protected second rounder. The spindly ball-handler only landed in Boston originally because the Raptors, who drafted him in the second round in 2021, had already given up and the Celtics took a flier on Banton. That’s the guy who’s going to revolutionize NBA basketball?

But then you remember that some of the best closers to ever pick up a baseball were failed starters. You might know Mariano Rivera. He’s a pretty famous example. Joe Nathan. Jonathan Papelbon. Robb Nen. No one knew they were gonna be all-time great until they gave up the starting profession.

Banton’s been here. Last season, he was a revelation, averaging 18.7 points after March 1 mostly off the bench as the second unit spark plug. I wondered during last season’s broadcasts if he could break into the Sixth Man of the Year conversation this year if he kept it up.

I don’t want to make too much of a three-game sample, but it’s enough for me to wonder why closers don’t exist in basketball. Banton has been that dominant. It looks almost effortless the way he’s glided into the paint every time down the floor. It occurs to me that maybe it looks effortless because defenders become effortless when they’re tired.

There is something there, I think. Some slack that needs tightening.

Good players want to be the starters. That’s where the money is. The ones who log the big minutes and carry the team throughout the game. How good could a guy be if he just shows up at the end of the game? If the player was so good, why couldn’t he play all four quarters?

That sounds a whole lot like the way Major League Baseball traditionalists might have talked about it 70 years in.

Jerome Holtzman was the first whistleblower on Bob Rosenberg, the Bulls stat-keeper for Michael Jordan during his fishy DPOY season, well before he was the statkeeper for Michael Jordan. “[Holtzman] was always accusing me of padding the assist totals for [ex-Bull] Guy Rodgers,” Rosenberg told the Chicago Tribune in 1990. “Every time, he’d introduce me to people with: ‘This is the guy that made Guy Rodgers famous in the NBA.'” Small world.

Wilhelm, the famed knuckleballer, was Mariano River’s first minor-league coach with the Yankees. Huntersville, NC standup! OK, enough about the Yankees.

Just wanted to say, in case you weren’t picking it up: the Blazers broadcast folks are the best.

The closer was one a of a million things that decreased the watch ability of baseball. God help us if this is the future of our beautiful game.